Guys, you're getting older.

Unless you've got a portrait in your attic that's aging in your place, it's a fact you'll have to get used to. And in many ways, it will be great: You'll get wiser. You might advance in your career and make more money. Plus, a little gray hair can make you look more distinguished.

But not every change to your body is going to be so fun. Each decade, your body is going to be different: more of this, less of that. Adding the right exercises to your routine to address these changes can help reduce or even reverse the damage that aging will cause. Use these moves suggested by top trainers to help you face each change with confidence and build a healthier body every year. With their advice, your best days will always lie just ahead.

Decade: 20s

The Change: You sit a lot more.

This one won't apply to every single guy in their 20s, but if you get a job behind a desk, all that sitting can start adversely affecting your health. According to the American Heart Association, the average American under the age of 60 spends six to eight hours per day on their butt, which can make you more likely to die of a heart attack. In on study from 2009, people who sat half the day were found to be 54 percent more likely to die of a heart attack, regardless of what they did the rest of the day's hours.

Sitting can also have a deleterious impact on your mobility and flexibility, meaning that when you do get out of that chair, you won't be able to move your body as well—which could keep you from wanting to exercise. The effects of being seated all day start "from the head on down," says Sarah Feilders, a flexibility coach and expert in Montreal who shares weekly stretch-along videos at her blog, Sarah's 60 Second Stretch. "It can create a forward head posture that can create pain and stiffness in your neck, [and] hunched shoulders, which can weaken your middle back muscles. It also creates stiff hips, which can lead to lower back pain."

The first solution to this problem: Avoid sitting as much as you can. See if your company will give you a standing (or adjustable) desk. Take conference calls and other phone calls while standing up. Walk to a coworker's office to talk through an issue rather than sitting and emailing them. Or just take frequent standing breaks to get out of your chair—scientists at the University of Missouri say standing can help restart fat burning enzymes that are turned off while you're seated.

While you're out of your chair, Feilders recommends trying a few simple movements to help undo some of the hip- and upper back-tightening effects of being seated.

For your hips, try a kneeling hip flexor stretch. Get on one knee with your other foot flat on the floor so that your knees both form 90-degree angles. Keeping your hips square, push forward slightly into your front knee until you feel a stretch in the hip of your leg that's on the ground. If you're not feeling a stretch, try resetting, moving your back knee backwards just a touch, and squeeze your butt slightly as you stretch. Hold for a few seconds, repeat and switch sides.

For your upper body, Feilders suggests an active chest stretch. To do this stretch, stand with feet about shoulder-width apart, knees bent slightly, arms at your sides. Keeping your right arm straight, lift it up past your head, then reach and bend your elbow as you press your hand back behind you. Return the hand to start and repeat.

Decade: 30s

The Change: Your aerobic capacity starts to slip.

Aerobic capacity is a measurement of the amount of work your body can do using a certain amount of oxygen—or how efficiently your body can use oxygen to do physical work. Once you hit your 30s, regardless of your physical activity habits, it's going to start declining, according to a study published in the American Heart Association journal, "Circulation."

It's also the experience of guys in their 30s: This is the age when guys start to complain that they can't run or play as hard as they used to. For Mike Wunsch, a lifelong basketball player and a trainer and program designer at Results Fitness in Santa Clarita, California, it meant planning his physical activity around basketball games to make sure he could be at his peak when he hit the court.

"I would definitely plan how and when I'd lift. I'd plan my entire week around having one game per week," says Wunsch, 39, who says he could dunk until he was 35—but no longer. "I'd lift two or three days before, and be very proactive about my recovery."

To help increase aerobic capacity—or at least maintain it—Wunsch suggests guys in their 30s make sure to "put in the mileage," but also try some interval circuit training, where bouts of strength work are alternated with short bouts of rest. To keep this going and to train the heart, Wunsch recommends keeping your heart rate in the 130 to 140 range throughout your work and rest periods.

One exercise Wunsch would prescribe for such a circuit is a goblet squat, a squat variation where a dumbbell is held in front of the chest. "It's easy to do, requires minimal equipment and a very large return on investment," he says. You're moving lots of joints and using lots of muscles, so this move is also very taxing on the heart—which you want when trying to increase aerobic capacity.

Try this simple timed interval circuit, attempting to keep your heart below 140 beats per minute throughout. If you don't have a heart-rate monitor, think of trying to keep your heart in the range you'd feel while running at a slightly-higher-than-medium pace—not sprinting, but not able to easily hold a conversation either.

Perform each of the exercises listed below for 10 seconds, then move to the next exercise. After completing all three, rest for 20 seconds, or until you return to the heart-rate range described. Try completing the whole circuit four times to start. Over time, try to add more circuits and increase your repetitions of at least one exercise.

Your aerobic capacity circuit includes:

1. Goblet Squat: Stand with your feet hip-width apart, toes pointed slightly out from parallel. Cup one end of a dumbbell in both hands in front of your chest with your elbows pointing down—in this position, the dumbbell and your arms will look like a goblet. Push your hips back to initiate the squat. Bend your knees to descend until your thighs are at least parallel to the floor, keeping your chest up and your weight back on your heels. Keep the weight of your body in your heels and press back up to standing.

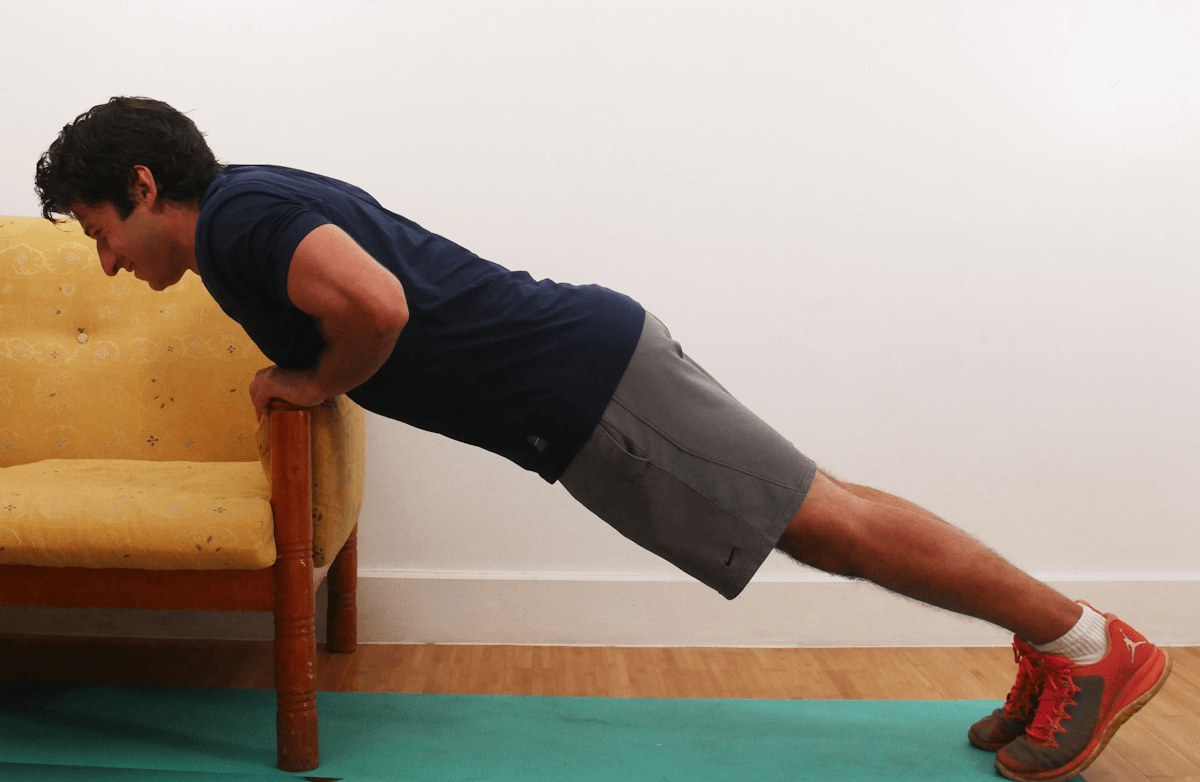

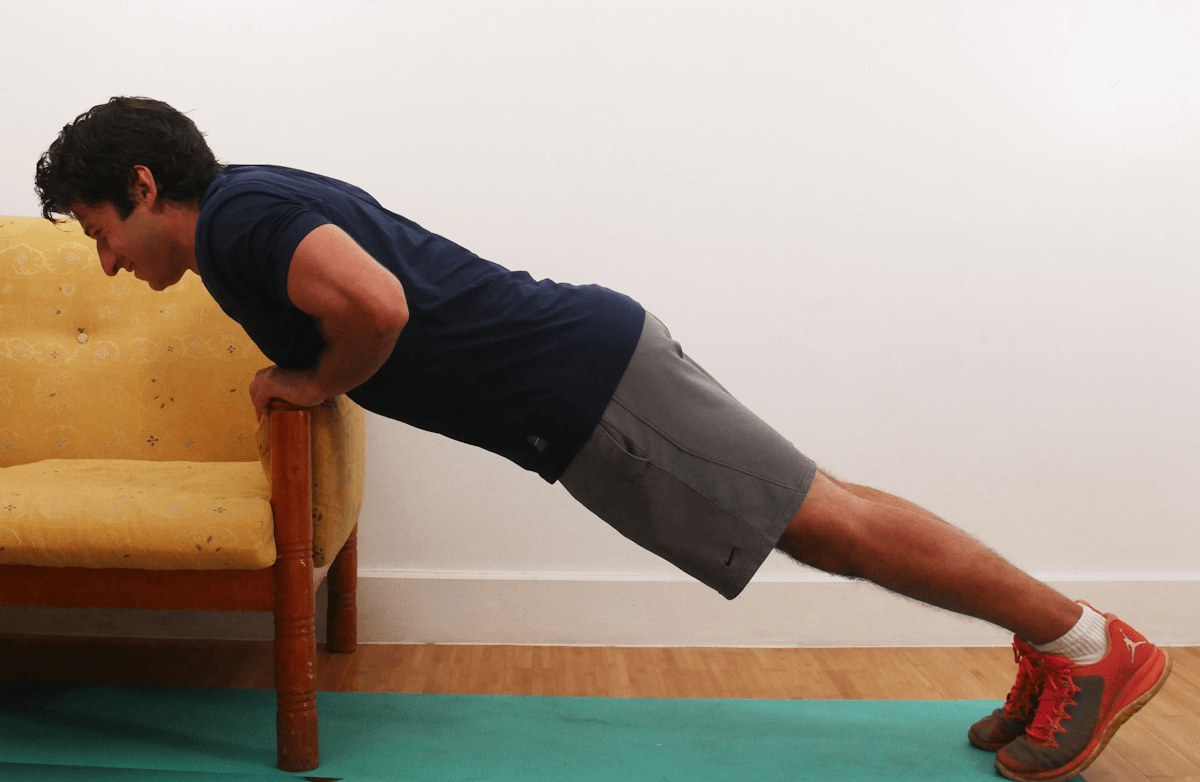

2. Elevated Pushup: Place your hands shoulder-width on the arm of a sofa or the second step of a staircase. In this position, assume a straight body line from head to heels. Bend your elbows to lower your body until your chest reaches your hands, maintaining the rigid body line throughout the movement. Press back to start, maintaining the body line.

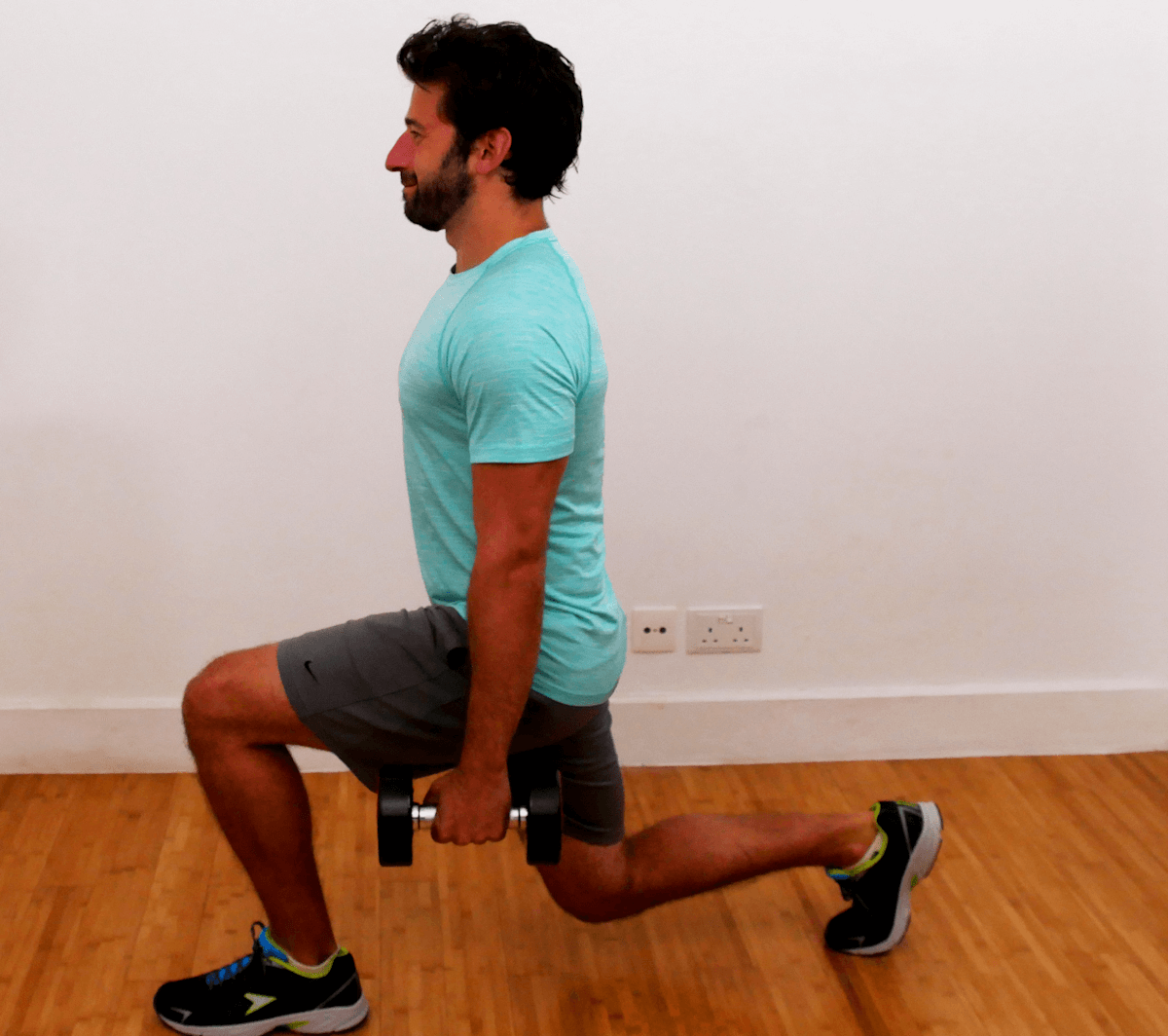

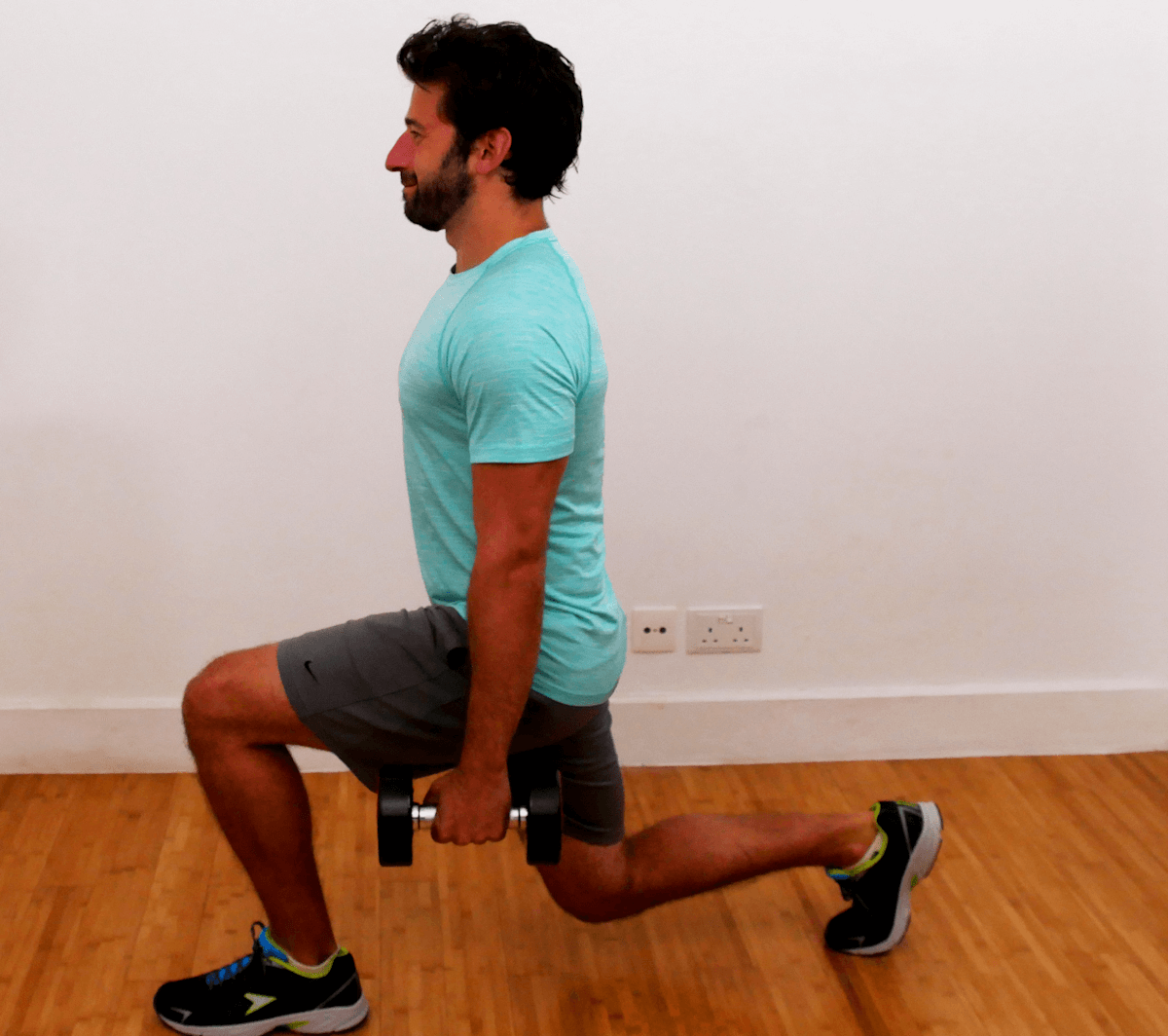

3. Forward Lunge: Stand with your feet shoulder-width apart, holding dumbbells at your sides if you choose. Take a large lunge step forward with your right leg, descending as you step until your knees both form 90-degree angles. Press through your right foot to stand back up. Repeat with your left foot.

To see if your aerobic capacity is increasing over time with these circuits, you can measure your work capacity. While keeping your heart rate in this range, see how many reps you're doing in each round of a circuit. When the number increases while your heart's in the same range, your work capacity for that time period has increased—meaning your aerobic capacity has likely increased as well.

Decade: 40s

The Change: You're losing muscle mass.

As they age, both men and women suffer from sarcopenia—a loss of muscle mass. It can fall as much as one percent per year in your 40s and 50s, leading to a loss of muscle as high as 30 percent between your 40s and your 60s.

"[The solution] is really simple. It's just 'lift weights,'" says Shawn Arent, PhD, director of Kinesiology and Applied Physiology graduate program at Rutgers University. You can't stop muscle loss completely, as it's just part of aging, but you can minimize the effects. "If you lift weights, if you apply an external load, you can dramatically prevent [muscle loss] for a period of time or slow it down significantly so you don't have a loss of function over time."

Arent says that when it comes to maintaining lean muscle tissue, your body doesn't "know" the difference between whether you're lifting via a machine or with free weights, but barring an injury that prevents it, he suggests performing multi-joint lifts with weights. "[Lifting weights helps] maintain posture and load the spine and limbs," he says. Not only will these exercises use the most muscle during the movement—triggering more growth per rep—but "they're going to benefit you most structurally, as well." That is, performing these kinds of lifts can help maintain bone mass as well as muscle mass.

Arent recommends three exercises in particular: deadlifts, like the stiff-legged deadlift described below, as well as squats—like the goblet squat described above—and rows. For all these moves, the weight doesn't have to be overly heavy, Arent says. It's more important that whatever weight you choose, you perform the exercise until you're worn out—nearly to technical failure, where you can't do more reps with proper form. In recent studies, lifting to failure with lighter weights had the same effect on muscle size and strength gains as lifting heavier weights. In one study published earlier this year in the "Journal of Applied Physiology", men who lifted 75 to 80 percent of their one-rep max (the amount you could lift for just one repetition) for sets of eight to 12 gained similar size and strength as guys who lifted 30 to 50 percent of their one-rep max for 20 to 25 repetitions per set.

"In other words, if you're going to use lighter weights, make sure you make it hard, and don't just do 10 reps that are pretty easy and say, 'I'm good, I lifted,'" Arent says. Make sure the set makes you tired so you can force your muscle to adapt. Try three sets of each of these three exercises to start.

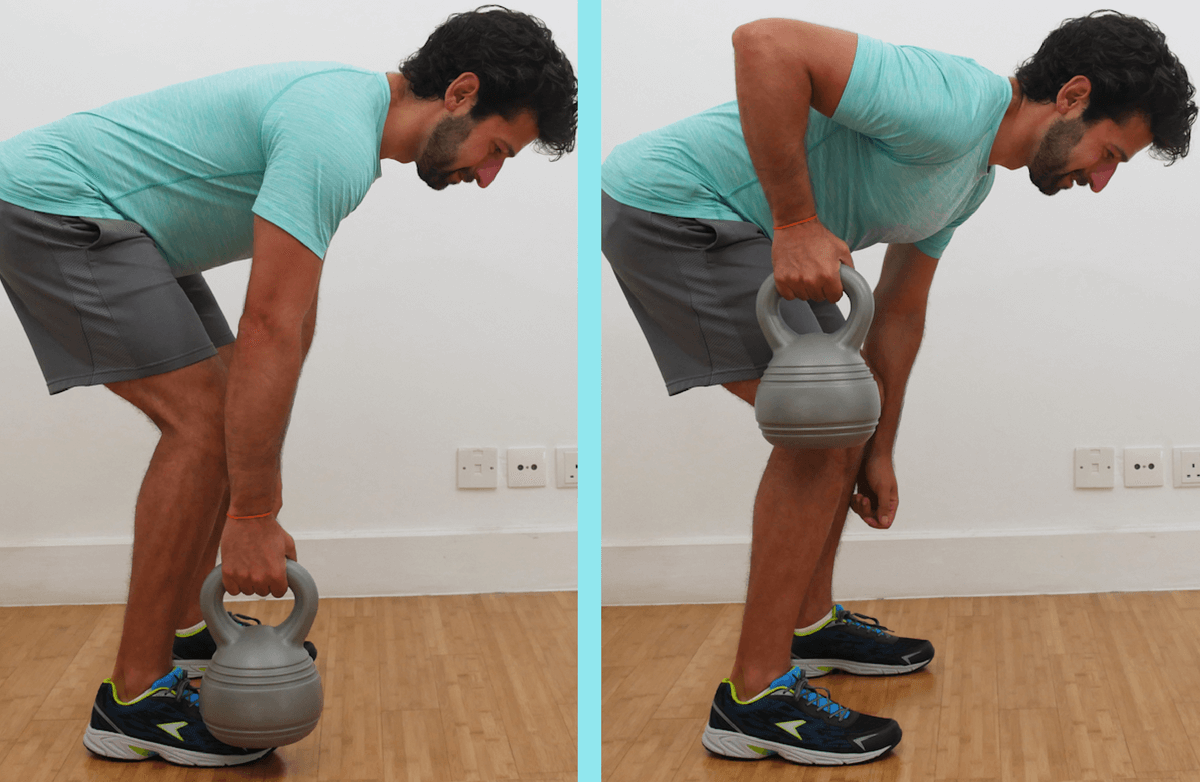

1. One-Arm Bent-Over Row: Stand holding the weight in your right hand with arms at your sides, feet hip-width apart (or staggered depending on your comfort level), knees slightly bent. Push your hips back like you're opening a door behind you with your butt. This starts the hip hinge. Keep pushing your hips back so that your back remains flat until it is nearly parallel to the floor with the weight hanging straight down from your shoulder. Maintaining this flat back position, pull your right elbow straight back until your hand reaches the side of your chest. Lower the weight back to the starting position, and repeat. Do all your reps on the right, then switch sides and repeat.

2. Goblet Squat: (pictured above) Stand with your feet hip-width apart, toes pointed slightly out from parallel. Cup one end of a dumbbell in both hands in front of your chest with your elbows pointing down—in this position, the dumbbell and your arms will look like a goblet. Push your hips back to initiate the squat. Bend your knees to descend until your thighs are at least parallel to the floor, keeping your chest up and your weight back on your heels. Keep the weight of your body in your heels and press back up to standing.

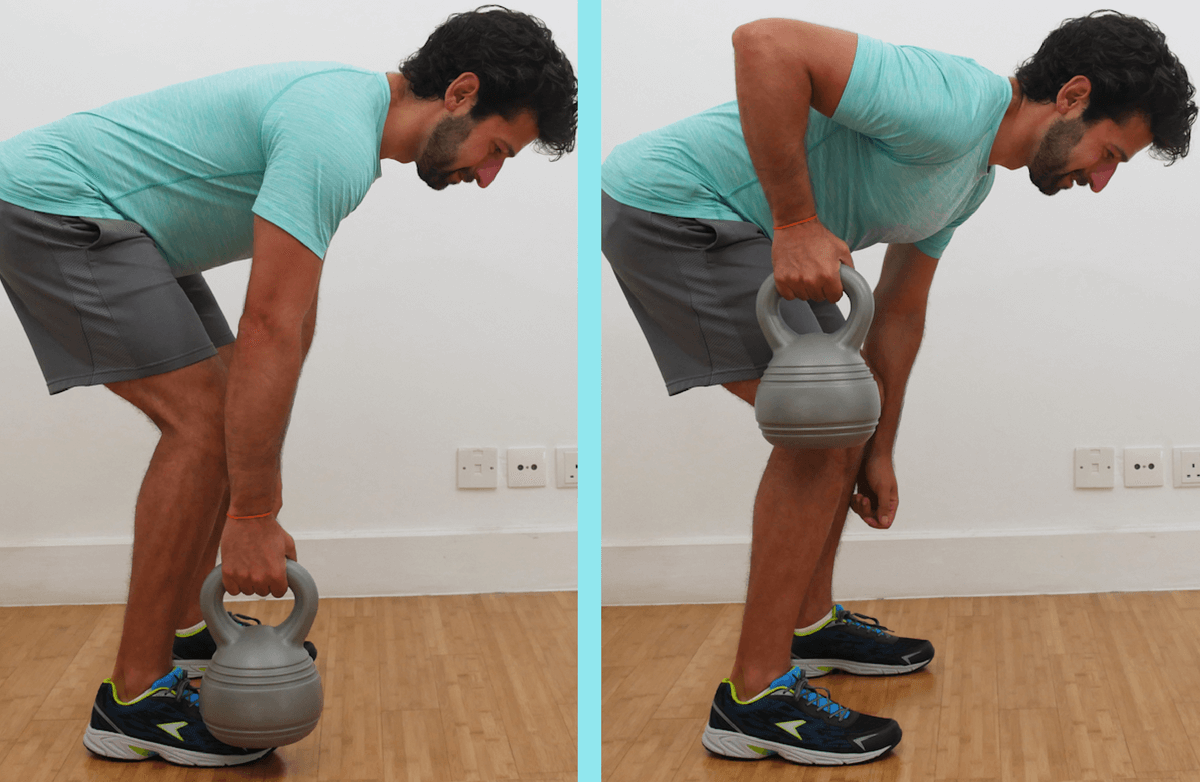

3. Dumbbell Stiff-Legged (or Romanian) Deadlift: Hold the dumbbells in front of you, palms facing the front of your thighs. Push your hips back to bend at the waist and lower your body until your back is parallel to the floor. Let the dumbbells hang down as you bend, maintaining a flat back. Thrust your hips forward to return to standing to complete one rep.

Decade: 50s

The Change: Dropping testosterone.

Drops in testosterone actually start in your late 30s, with research showing levels falling one to two percent per year in your 40s. But the effects of this gradual decline don't seem to hit until the fifth decade, when symptoms, including lost libido and reduced energy, start to rear their ugly heads.

But while heavy weights can give you a T bump, the effect is too short-lived to change the chronic state of decline, says Arent. "You might get a one to two hour uptick, but that's not changing chronic testosterone production," he says. In order to fight back, "you need to create an up-regulation in basal free testosterone."

While hormone replacement therapy might be the fastest way to get this effect, there is another way to stem the tide: lower your body fat percentage. "A higher level of body fat is associated with blunting of free testosterone levels," he says. More fat can also mean more estrogen in your body.

Another factor that can be increasing your loss of testosterone: too much cardio work. "I'm not against cardio by any stretch," he says, "but a moderate amount that helps with overall fitness is the critical part here, not an excessive amount that can potentially blunt free testosterone."

To combat this, Arent recommends lifting weights—for its fat-burning and lean muscle-preserving benefits—and changing the way you do some of your cardio work. Instead of doing all cardio as medium-paced, steady-state work, try incorporating circuits of strength exercises or performing interval cardio, alternating bouts of fast and slow work, which has been shown in multiple studies to burn more fat than steady-state road work.

Try this interval routine: Using the cardio method of your choice, warm up for two minutes at an easy pace. Next, speed up and perform the exercise at a perceived level of exertion of eight out of 10 for 60 seconds. Slow down and do the exercise at a perceived rate of three out of 10 for 60 seconds. Repeat this sequence of hard work followed by easy work for six rounds. If this is too difficult, start out working at the eight level for 30 seconds. Over time, instead of adding more intervals, increase the amount of time you work and reduce the time you rest.

Decade: 60s and beyond

The Change: You're at greater risk for a fall.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, one out of four Americans aged 65 and older fall each year, resulting in 2.8 million trips to the emergency room, 800,000 hospital admissions and more than 95 percent of hip fractures. Falls don't just cause broken bones, but they are also the biggest cause of traumatic brain injury in the country.

One reason Wunsch suspects older clients are susceptible to falls is they can't recover when they start to fall—they don't have the muscle power to react quickly to produce the force needed to keep themselves upright. Muscle loss over time comes disproportionately from fast-twitch muscle fibers, which are responsible for this power. In fitness, power measures not how much force a muscle can produce, but how fast it can produce that force.

To maintain and develop that power, Wunsch has clients do medicine ball power work. One easy exercise is a medicine ball chest pass: Holding a medicine ball at the chest with both hands, press both arms forcefully forward to push the ball away from you, either to a partner or a nearby wall. Retrieve the ball, reset and repeat. This exercise can be done standing or, if necessary, while seated. Perform five to eight throws total.

Falls can also be prevented with improved balance. Feilders helps older clients improve their balance with a ballet-inspired heel lift exercise. To do it, stand next to a wall or chair, resting your hand for support and balance help. Your feet should be shoulder-width apart, either parallel or at a slight diagonal. Lift the heels to raise the body towards the ceiling, controlling the movement on the way up. Go as high as you can, pressing through the middle toes to put weight on the balls of the feet. Then, instead of just falling back down, control the descent, returning to standing normally before really pressing the feet back into the ground. Repeat five to eight times.

Aging is what you make it, and with the right mindset and exercises every decade can be your best decade yet.

|